The day dawned bright and clear once again, with the fleet warned that the 25th of May was Argentina’s national day and an extra weight of attacks could be expected (in fact by this point in the war the Argentine’s losses were beginning to seriously reduce their capability – of the 27 Dagger flights sent to San Carlos in the last handful of days, 10 had failed to return – so any extra effort was mostly imaginary). After requesting a patrol line further away from land and it’s handicapping effect on radar effectiveness, Coventry and Broadsword were given a compromise position – approximately 8 miles north of Government Islet, running an east-west patrol line that took them to the north of Pebble Island at around 10-15 miles distance. This gave the radars clearer sky in all directions but to the south, and enabled them to give 30 miles worth of additional warning to the ships in San Carlos. However, it also put the pair of ships further away from Sea Harrier cover, and the additional distance degraded radio comms with the San Carlos group. 15 miles had been the previously assessed minimum distance from land for a successful Sea Dart engagement against attacking aircraft – this was pushing the system to its limits.

Raids on San Carlos

The first Argentine raid of the day was to be aimed at the San Carlos area, departing Rio Gallegos at 08:10 local (11:10Z). Two of the four aircraft experienced problems and turned back, with the remaining pair continuing on. After aerial refuelling, the pair approached West Falkland and attempted to enter San Carlos from the north – which would have led them right into our missile trap. Luckily for them, they met some low cloud and altered their route, putting Pebble Island between them and us. That was the end of their luck, as they turned into what they thought was San Carlos Water and the first ship they saw was white with big red crosses on – SS Uganda, which as a hospital ship they could not attack.

In fact, they had flown into Grantham Sound, and continued on to Goose Green and made a strafing run against one of their own ships, then a strafing run against some of their own troops, then got fired at by their own anti-aircraft artillery (damaging one of them, Capitan Hugo Angel del Valle Palaver’s C-244). The pair split to take different routes back to Argentina, one going south… and Palaver, running low on fuel, choosing the slightly shorter route back to tanker support to the north.

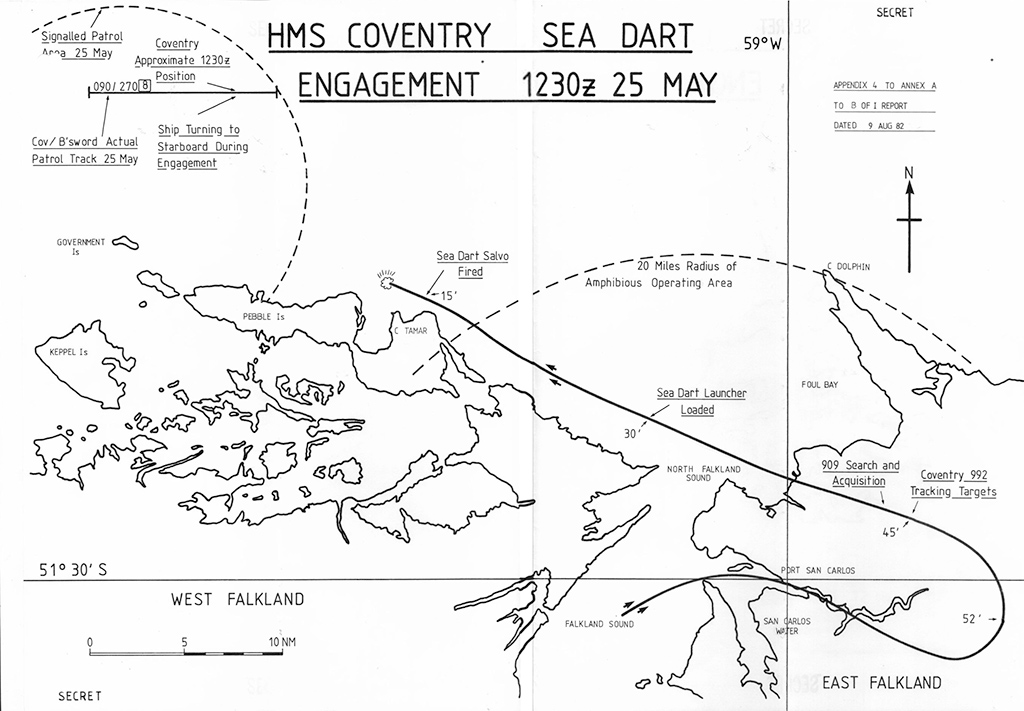

As his Skyhawk climbed away from the islands it was locked on to by Broadsword’s Type 967 radar, the target (assessed as potentially being a pair) was passed to Coventry by the Link system and Coventry fired a pair of Sea Darts at 09:30 local (12:30Z – the salvo being an effort to make sure at least one target was hit after the disappointing sequence of misses on 9th May). Unfortunately, the luckless Capitan Palaver did not survive this encounter. Broadsword reported a parachute had been seen, whilst Coventry’s own gun crews reported seeing a ground impact – prompting Coventry’s crew to think they may indeed have hit a pair of targets rather than one. Ominously, Coventry’s communications intelligence section picked up radio comms that indicated that their position had now been reported by the surviving Skyhawk from this encounter.

Later in the day, Coventry detected another raid developing. This raid, Toro Flight, which had taken off at 11:30 local (14:30Z) and consisted of 4 Skyhawks, disappeared from view over West Falkland, and entered San Carlos Water from the south. One of them was immediately shot down by HMS Yarmouth’s Sea Cat (a rare kill from this old missile, also claimed by a Rapier battery and some Royal Marines blazing away with their rifles), and the pilot ejected into captivity. The remaining three attempted to attack HMS Plymouth and HMS Arrow, one suffering jammed cannons and another failing to release his bombs due to a fault. Both ships escaped damage. The trio exited San Carlos to the north and once again, as they climbed to go home, Broadsword’s Type 967 radar picked them up and they passed the targets to Coventry over the Link system.

A single Sea Dart was fired this time, at 12:30 local (15:30Z) and Capitan Jorge Osvaldo Garcia’s Skyhawk C-304, climbing higher than his colleagues whilst he dealt with a hydraulic problem, was hit shortly after passing Pebble Island’s coastline. He ejected successfully, but sadly was not recovered from the water, and his body washed ashore in his dinghy at Golding Island in 1983.

A further raid warning sent from HMS Plymouth around 13:00 local (16:00Z) triggered Coventry and Broadsword to go to action stations once again a short time later; however, this was based on mistaken identity of the radars of an approaching pair of Sea Harriers and the ships soon returned to defence stations.

Vulcano and Zeus Flights

It was 2-nil to Coventry so far. The next raid, taking off around an hour later, was specifically tasked with hitting Coventry and Broadsword, and unfortunately had more luck. Split into two flights of three, ‘Vulcano’ and ‘Zeus’ flights, this was already an indication that Argentine efforts had begun to suffer – most previous Skyhawk raids had been planned with 4 aircraft each, not 3.

Vulcano flight took off a little before14:00 local (17:00Z) missing one aircraft which had become unserviceable. Zeus flight also became short one aircraft shortly after departure as his VHF radio failed. The remaining four Skyhawks flew on. The surviving Skyhawks of earlier raids had reported the ships’ general positions, so spotters were tasked with climbing to high ground on Pebble Island and radioing an accurate position report to a Learjet (callsign ‘Ranquel’) that was orbiting well to the west out of missile range. With this position report in hand, a route was chosen to mask the raid’s approach and use the Argentine’s knowledge of the limitations of the Type 42’s radar systems. British assets near the Argentine coast – likely a submarine – reported the raid’s launching, and Coventry went to Action Stations at 14:15 local (17:15Z).

Initially detected by Coventry’s long range Type 965 radar 160 miles away, whilst they were refuelling at 12:45 local (17:45Z), the raid was thought to be inbound for San Carlos once again, but could take either approach – north or south. The Skyhawks descended to extremely low level around 12:55 local (17:55Z) and disappeared over West Falkland, with Air Raid Warning Red declared. Instead of progressing south towards San Carlos as most prior raids had, this raid turned north towards Pebble Island – because it wasn’t heading to San Carlos. Minutes later, as they were crossing the western tip of Pebble Island just 10 miles away, Broadsword picked both pairs up again. Coventry’s radar was unable to pick up any of the incoming aircraft because of Pebble Island’s ground clutter.

Instead, her lookouts spotted the aircraft first, at around 8 miles distance. The aircraft had followed the coastline briefly before turning towards the two ships and so were on the starboard beams of the ships, which were progressing on the Eastern leg of their patrol line. The incoming 800 NAS Sea Harrier CAP (Neil Thomas in XZ496 and Dave Smith in XZ459) had been requested to come in towards the developing raid, but it was soon clear that they were too far away to the East, so were put into an orbit as Broadsword were confident that Sea Wolf could deal with the imminent raid.

Unable to get a Sea Dart firing solution, Coventry opened up with the 4.5″ gun, the starboard 20 mm Oerlikon, a light machine gun from the flight deck area along with numerous hand-held SLRs. The maelstrom of incoming fire – deliberately designed to put up a wall of shrapnel and shell splashes on the water ahead of the jets – impressed the two A-4 pilots sufficiently that – after a brief burst of cannon fire in our direction – they altered course away from Coventry and towards Broadsword, which they judged to be putting up less of a defence.

Broadsword, following us astern, now had a firm Sea Wolf lock. However, Broadsword’s 967 radar had a known issue – multiple targets in close formation would appear to the radar as a single contact. The pair of A-4s were so close to each other that it thought there was only one. Then one jet crossed rapidly in front of his wingman to widen their seperation from each other. Broadsword’s radar saw its contact split and the lock was lost. Sea Wolf, designed mostly to deal with single incoming missiles, went into a sulk – the launcher slewed to its stowed fore/aft position, and the crew frantically began working to direct the system towards the ‘new’ pair of targets. There simply wasn’t enough time, and with only a single 40 mm Bofors and some machine guns brought to bear on the incoming jets, this time the pilots weren’t quite so distracted.

Vulcano flight – Capitan P. Marcos Carballo and Teniente Carlos Rinke – both attacked the Broadsword. The Argentines had, as noted previously, become conscious of the ineffectiveness of many of their Mk.17 1,000 lb or M117 750 lb bombs, which were often passing straight through ships without detonating, or lodging within them but still failing to explode. As a result, Zeus flight were trialling the use of smaller bombs; low drag 250 kg (550 lb) bombs installed on a triple ejector rack under the Skyhawk’s belly. However, Vulcano flight were still carrying Mk.17 1,000 lb bombs – one each, as the Skyhawk could not carry three under the belly and the outer wing stations were needed for drop tanks.

The two aircraft of Vulcano flight therefore released one bomb each (not two or three each as is sometimes published); one missed entirely, the other managed to hit the Broadsword in the face of the Bofors cannon and small arms fire. This bomb bounced off the sea (twice!) near the stern, passed through the side of the ship and up through the quarter deck and flight deck, tearing the nose off the Lynx helicopter in the process, damaging the live torpedo mounted on the Lynx and starting a small fire. The bomb continued up and away from the ship, landing harmlessly in the sea nearby (accounts differ as to whether it then exploded or not). Once again a Mk.17 had failed to do its job despite hitting the target. Carballo’s windscreen had become obscured by sea salt during the low level flying in the run-up to the attack, and he describes releasing his bomb when the ship was dead centre in his windscreen, filling it entirely from left to right, so it is likely that his was the bomb that missed, and that it was Rinke’s bomb that hit Broadsword’s stern.

Target: Coventry

Zeus flight – Primer Teniente Mariano A. Velasco and Alférez Leonardo Barrionuevo – were close on the previous raid’s heels and were visually sighted further East along the Pebble Island coastline than the previous raid. Coventry’s skipper had initially ordered a turn to port as the previous pair of Skyhawks had approached (at the end of the patrol line, to go back West), but to keep the incoming aircraft on the starboard beam, this was changed to a turn to starboard. More aircraft were now reported to the north-west – this was likely to have been the pair that had attacked Broadsword climbing and turning to go home, but they threw further confusion into the mix regardless.

With the missile team working frantically to get a Sea Dart away at the second pair of aircraft, they were indeed successful with acquiring a lock and the call of ‘Birds Affirm’ was made in Coventry’s Ops Room. Once again, Coventry and Broadsword declined assistance from the Sea Harrier CAP, much to the pilot’s vocal disgust, as they had left their orbit and progressed further towards the two ships in the meantime, and were now within seconds of being able to take a Sidewinder shot. The judgement was that the engagement would happen practically overhead the two ships – far too close for comfort, and with Sea Dart apparently locked on and Sea Wolf also ready to go, the SHARs also needed to be kept clear for their own safety.

In fact the 909 radar only had a brief lock, and the lock was almost certainly on a ground return from Pebble Island. The Sea Dart was fired regardless, more in hope of deterrence effect than any expectation it would now hit a target. Both A-4s, unaware the missile was unguided and not even pointed in their direction, turned hard left to avoid it, but it passed harmlessly some 300-500 meters away from them, ending up spearing into a peat bog on Pebble Island (from where it was recovered after the war – it is now on display in the Explosion Museum of Naval Firepower in Gosport). Then the Skyhawks turned hard right back towards Coventry.

1: Coventry’s last Sea Dart, being fired unguided.

2: Location of the locked on A-4, obscured by forward 909 dome

Broadsword’s Sea Wolf had locked on, but as Coventry turned further to starboard, heading nearly due South, she crossed in front of Broadsword’s line of fire. Her Sea Wolf tracker lost lock and she was unable to fire for fear of hitting Coventry instead. The two A-4s – armed with three lighter bombs each rather than the single heavy bomb carried by each of the previous pair – were now only seconds away, and Coventry’s fate was now in the hands of the guns on her port side, that had so far been untested.

Unfortunately, a fault in the port lookout aiming sight led to the main 4.5″ gun being given erroneous target elevation angle information, and as the gun slewed around to the port side, it also depressed to the point that it was firing below the incoming jets and after 3 rounds were sent into the sea well ahead of them, it was stopped from firing whilst an effort began to get it pointing in the right direction. Then, Coventry’s port Oerlikon 20 mm cannon jammed. In desperation, an attempt was even made to order the use of a signal projector lamp to try and blind the oncoming pilots (the signal projector operator was unimpressed with this idea). The call of “BRACE BRACE BRACE” was made on the ship’s broadcast system and shouts of “TAKE COVER!” rang out around the ship.

16 seconds after Coventry’s last Sea Dart had been fired, Velasco fired his cannons, possibly aiming for the bridge, but if so, the ship’s continuing turn spoiled his aim. Instead, he sprayed the entire ship’s side from just aft of the bridge to the quarter deck, mostly hitting the hangar and quarterdeck area, luckily without casualties. Then he pressed his bomb release. Coventry’s luck had completely run out and all three of his bombs, released at just the right moment, hit the ship, carving a path of destruction deep into the interior. Velasco’s 250 kg bombs had all come to rest within the ship instead of tearing straight through, due to their lighter mass compared to the Mk.17 bombs. Barrionuevo, just behind him, witnessed his leader’s bombs striking Coventry’s hull.

The first bomb hit the port side of the hull, about 3 feet above the waterline, below the bridge (just under where the painted-out D118 pennant number was beginning to show through once more), passing through the computer room and lodging in the conversion machinery room below. The second bomb entered through the side of the superstructure just forward of the life raft stowage and tore through the main fore/aft passageway, breaking a hydraulic ring main and starting an immediate fire and passing through the naval store room below before probably lodging in the provision store below that. The third bomb hit the outer deck edge in the area of the Olympus engine intake grilles – outboard of the foremast – and lodged in the aft part of the forward (Olympus) engine room.

Seconds later, Barrionuevo’s Skyhawk flashed across the top of the ship – but despite pressing his bomb release, none of his bombs left his aircraft. Two witnesses onboard Coventry reported a single ‘bomb’ tumbling overhead at this stage, however – it may have been that this second Skyhawk released a drop tank in error.

On 25 MAY six of us departed Rio Gallegos but two aborted with problems. The four of us headed north towards the island of Borbon (Pebble Island). At about 15 to 20 miles in the open sea north of the islands we saw two frigates on our left, which I pointed out to the leader – the two aircraft ahead attacked the frigate that was toward the west and cruising toward the continent. The other two headed for the frigate that was directly ahead (we didn’t know which one it was). Then we heard the first flight was attacking, we (the last aircraft) separated about 4 miles from the frigate that was to the left. We saw something very tiny and I told the leader “There, to the left, frigate! What do you think that is?” It was the ship. He looked at it and replied “Yes, those are the ones”. As we began our run (one minute out at top speed) they fired a missile. I don’t know what type of missile it was; perhaps a Sea Dart because the frigate was of the 42 type, which turned out to be the Coventry. The missile passed over us at about 300 to 500 meters. Once I framed the ship in my sight, I saw nothing else for about 30 seconds, but I felt something like the impact of cannon fire before releasing my bombs. As we were coming toward the frigate, we noticed it began to quickly change course by 90 degrees. By the time I released my bombs, I was 40 degrees off from the ship. We passed over the ship and noticed three bomb hits on it. As I came back down to just over the water, I saw the other two A-4s had escaped successfully. I caught up with them in front of me, and we returned together.

Post-war interview with Alférez Leonardo Barrionuevo (National Archives file AIR 20/13030)

Note that they misidentified both ships as frigates and his bombs did not in fact release from his aircraft.

“Coventry’s blown up”

Velasco’s bombs were fitted with delay fuses, so several seconds of deathly silence elapsed within the ship and just as the first damage reports were being made reporting the holes the cannon shells and bombs had torn in various decks and bulkheads, the first bomb went off, tearing a hole in the ship’s port underside, destroying the conversion machinery room and computer room above, with the explosion boiling up through the computer room hatch to wreck the operations room, injuring and badly burning many of the occupants. Simultaneously, the third bomb – in the forward engine room – went off, tearing a large hole in the hull below the waterline and two smaller splits in the ship’s side below the Cheverton motor launch davits and killing several of the crew, mostly in the auxiliary machine room, forward engine room itself and the junior rates’ dining hall above (where one of the first aid parties had been stationed). The blast tore a hole in the bulkhead between the forward and aft engine rooms, allowing the fireball to enter the aft engine room too, injuring one of the occupants.

Fires immediately took hold and water began pouring into the ship through the hole ripped in her hull, below the waterline. Electrical power was lost from some forward areas of the ship. Both the Tyne engines declutched from the gearbox and the ship rapidly came to a halt, aided by the drag of the torn open hull. The forward engine room was now open to the sea, and the bulkhead between the fore and aft engine rooms was also holed. There was no amount of damage control effort that could save her now, and HQ1 – the primary area to run damage control from – was without power and rapidly filling with smoke from the adjacent fires. HQ1’s loss also cut communications between the forward and aft damage control bases.

The ship immediately began to list to port, and the weight of incoming water was soon added to as the entrance hole from the first bomb, just a few feet above the waterline, became submerged. Ventilators throughout the ship had been crash stopped just before the bombs hit – a lesson learnt from Sheffield’s loss, where smoke had quickly been drawn through the ship by her ventilation system. This thankfully kept much of Coventry’s compartments relatively smoke free and with her diesel generators still running, the lights were mostly still on too – valuable assistance to the crew, now dealing with an imminent need to escape.

Back on the flight deck, the Ship’s Flight crew were busily clearing debris in an effort to get the Lynx flashed up and airborne, but the Lynx was heavy with full fuel and 2 Sea Skua missiles and despite getting the engines started, the list was soon beyond safe take-off limits. Releasing the harpoon holding the helicopter to the deck would have resulted in the heavy helo sliding straight off the deck. They shut down without ever engaging the rotor blades.

While the second bomb had not gone off, the hole it ripped through the decks helped to allow smoke and fire to quickly spread, and as she was rapidly listing to port from the flooding into the engine rooms, this large hole was soon itself at water level and further accelerated the flooding into the main 2 deck passageway. Bulkheads along this passageway were not fully watertight, with various holes cut for pipes and cabling not sealed where these services went through (only the more recently built HMS Exeter had full seals in these areas); this led to the 2 deck passageway flooding from end to end.

Within 10 minutes, the ship was listing to port by 15-20 degrees. The large number of holes torn by the shrapnel from the bomb explosions and cannon fire also became submerged and further added to the weight of water pouring into the ship. There is a possibility that the second bomb actually tore through the hull and went off in the water underneath the ship – some postwar video from dives appears to show significant denting to the hull undersides.

No ship-wide order to abandon ship was given – the confusion and chaos and total failure of ship-wide communications saw to that, but it was clear to everybody that Coventry was in an increasingly bad way and had to be abandoned. Quietly, efficiently, the crew nearest the upper decks struggled to release the starboard side life rafts – those on the port side were at too sharp an angle to be of any use now, but the starboard ones needed manhandling off their shelves to clear the decks below. Evacuation took place in an orderly fashion, while several members of crew were performing heroics rescuing fellow survivors from shattered and often burning or smoke-filled compartments throughout the ship.

Broadsword had immediately begun rescue operations using her ship’s boats, and helicopters also soon arrived from the ships in San Carlos Water – mostly “Junglie” Sea King HC.4s from 846 NAS onboard HMS Fearless. The reduction in the number of life rafts since the ship was commissioned now became an issue, as all the rafts on the port side remained lashed to their mounts and only the starboard ones had been released. Some of the rafts in the water became desperately overcrowded. Two life rafts drifted around the bow of the ship and as the ship rolled over, the Sea Dart missile on the launcher slowly cut through one life raft, putting all onboard back in the water once again – sunk twice in half an hour.

The actions of the rescue helicopter crews were magnificent – including hovering very near to the Coventry’s magazine (which could have blown up at any moment) to winch up survivors from life rafts next to the hull. One particular “Junglie” crew stood out, the crew being Lt Bill Fewtrell, CPO ‘Alf’ Tupper and WO John Sheldon. After sending Alf Tupper down on the winch to retrieve survivors and filling up their aircraft (ZA298) with 19 survivors (plus, sadly, the body of laundrymen Kyu Ben Kwo), Tupper volunteered to go back down1 and stay with the life rafts to manage the men still there whilst the helo returned to San Carlos. Tupper would receive the Distinguished Service Medal for his bravery in choosing to stay and assist other helos amidst the ever-present danger that the ship could have blown up.

Broadsword’s crew performed just as magnificently, with her ship’s boat and Gemini towing life rafts away from the Coventry as she rolled over despite the ever present danger of a major explosion – in fact one Gemini was pulled under whilst attempting to tow an overloaded life raft, adding her crew to those in the water and needing a rescue.

Less than an hour after the first bomb had hit the ship, Coventry had capsized completely. 17 of her crew had died in the ship; two more were killed in the process of abandoning her. As the sun set, her upturned hull, fires now quenched, faded into the darkness.

The Secretary of State for Defence, John Nott, caused a great deal of suffering back home that evening by announcing that a Type 42 had been hit and was ‘in difficulty’. With four surviving Type 42s down south, that meant more than a thousand families were worrying about their loved ones. Portsmouth was a tense and quiet city that evening. It wasn’t until around lunchtime the next day that next of kin were finally informed, and many were incorrectly told that their loved ones were missing. The media confirmed that the ship involved was the Coventry, in many cases before the Ministry of Defence had got in touch with the next of kin of the crew. Many of the ‘missing’ men were confirmed to be on the survivors list only after one more day of heartache for the families.

All four Skyhawks returned to base safely, though Carballo’s A-4 had one fuel tank holed by fire from the Broadsword. Barrionuevo’s bombs had failed to drop because of a suspected faulty landing gear lever microswitch – basically the aircraft thought it was still sat on the ground and so blocked the bomb release. He jettisoned them into the sea on his way home after disconnecting and reconnecting his weapons control panel. The pilot of the aircraft whose bombs sank Coventry – Velasco – was back in action two days later, carrying out an attack on the troops in Ajax Bay. HMS Fearless raked his A-4 with cannon fire, and his aircraft burst into flame. With hydraulics also lost, Velasco ejected over West Falkland between Port Fox and Port Howard. After two days walking he found an empty house which contained some food, and shortly afterwards met some kelpers. After unsuccessfully trying to buy a horse from them, he was dropped off at Port Howard. He took no further part in the war. The other three pilots on the raid also survived the rest of the conflict.

Worried about any possible Argentine efforts to send divers into the upturned but still floating ship, on May 26th a Sea Harrier was tasked with attacking the upturned hull in order to ensure that it would sink. Duly arriving over the given coordinates, there was no trace of Coventry, which had by this time already settled on the sea floor some 100 m below. The SHAR strafed the coordinates regardless – a job’s a job.

The Day After

The day after Coventry’s loss, the survivors were to be found spread among the Broadsword, RFA Fort Austin (the same RFA we had stored from enroute to the Falklands) and the hospital ship Uganda. Some of the more serious casualties had been airlifted to the field hospital at Ajax Bay. Later the survivors were consolidated and transported via helicopter or landing craft to Fort Austin and thence to safer waters East of the Falklands.

After that they were transferred by boat to the RFA Stromness, which sailed for South Georgia on the 27th of May. With the arrival of the QE2 and her cargo of soldiers on the 30th of May, Coventry’s crew were transferred to the QE2 and began the long voyage home.

They arrived to a hero’s welcome (see videos page) in Southampton on Friday 11th June. Three days later, the Argentines surrendered and the Falklands War was over.

Continue on to postwar events.

As you can perhaps appreciate, the day’s events were seen differently from many perspectives, and the final raid in particular was an incredibly intense and confusing set of events to everybody involved. Much that has been published about it contains errors, notably about the order of the Sea Dart kills on the day, the weight of the bombs that hit Coventry and the direction she turned just before being hit. The above account has been amalgamated from numerous sources including personal testimony of a number of the ship’s personnel and also the pilots on the raid, the board of inquiry report plus numerous published accounts that have all been found to contain some, sometimes minor, errors. I have used my best judgement as to which accounts can be trusted and/or verified against other accounts to produce what I believe to be an accurate story of the day.

Damien Burke

References

- Sheldon, J. (2021) Commando Helicopter Aircrewman. Air World, p.58.